SELECTED PROJECTS

MORENA LERABA

Through their analogue dissonance, these images question our relationship to the natural world.

![]()

MORENA LERABA

Exploring the majestic rural landscape of Lesotho and the urban density of Johannesburg’s inner city with Morena Leraba.

![]()

ALTER NATURE

Through their analogue dissonance, these images question our relationship to the natural world.

HUGH MASEKELA

A seven year chronicle of portraits from Masekela’s final years.

![]()

AUTO PORTRAITS

An exploration into the mechanics of memory and how we process the anonimity of the open road.

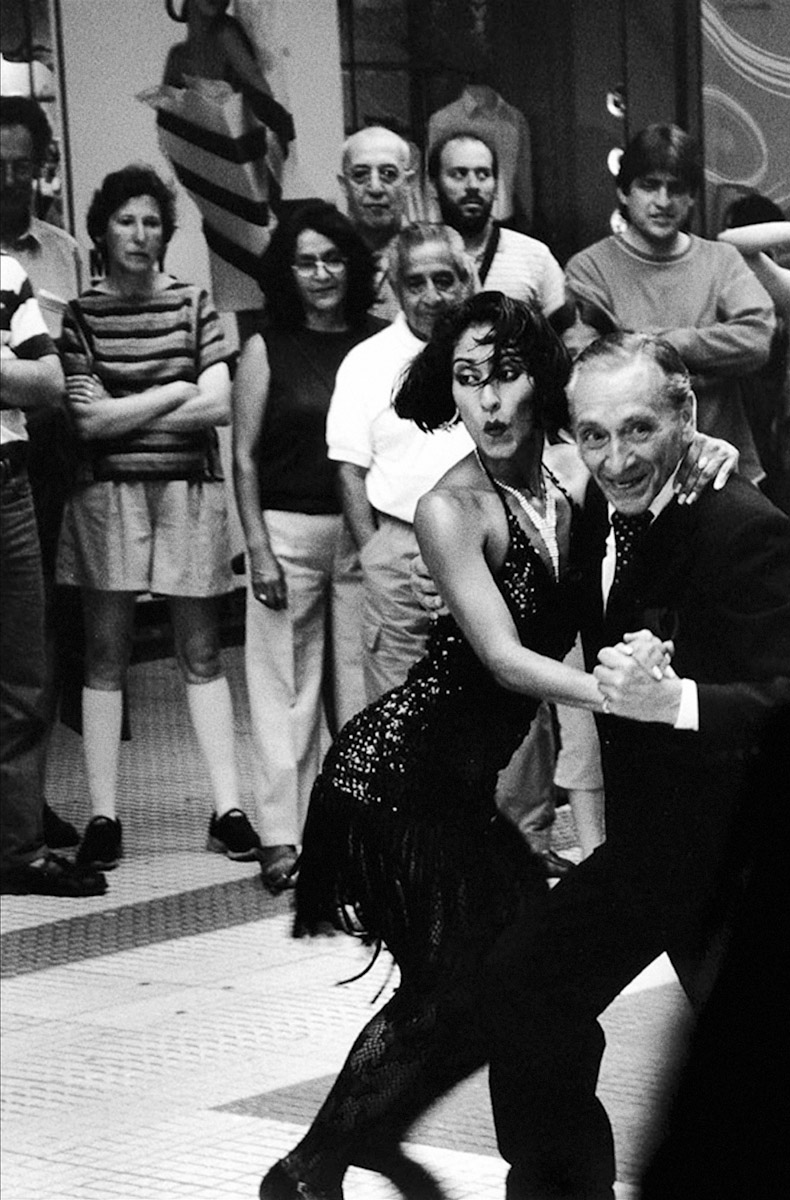

MORENA LERABA

2019 - ongoing

Teboho Mochaoa, known commonly by his stage name Morena Leraba is a Lesotho-born singer and rapper. He mainly uses traditional sesotho lyrics and combines them with electro, afro house and Hip hop. His lyrics are deeply rooted in Lesotho's traditional music, poetry, and its sub-genre, famo.

‘Fela sa Ha Mojela' is a 5-song EP by Morena Leraba, their first-ever release as a band after a series of collaborations and performances across the globe — meaning “song or poem of Ha Mojela” (in Sesotho language), these are some of the songs and ideas the band has been performing and developing throughout their 5-6 years in the scene. My portraits were used for the front and back cover of ‘Fela sa Ha Mojela’.

Listen to Morena Leraba here buy ‘Fela sa Ha Mojela here

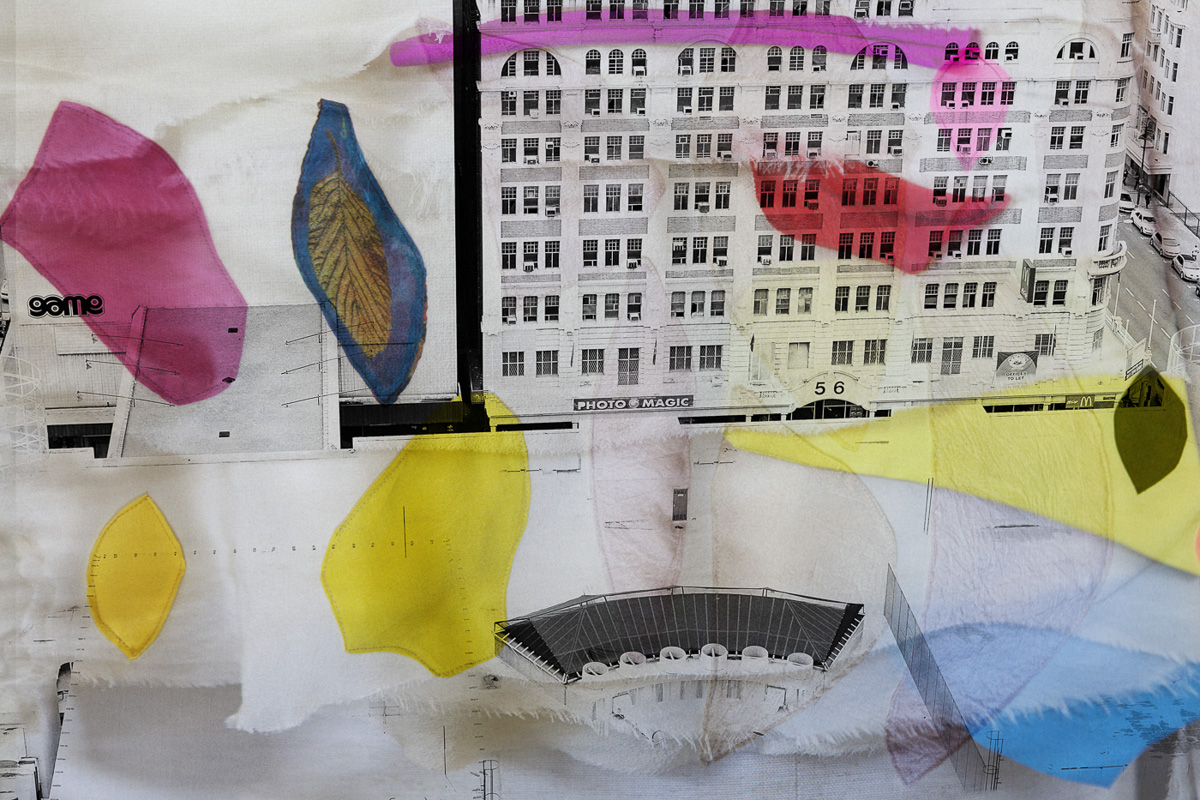

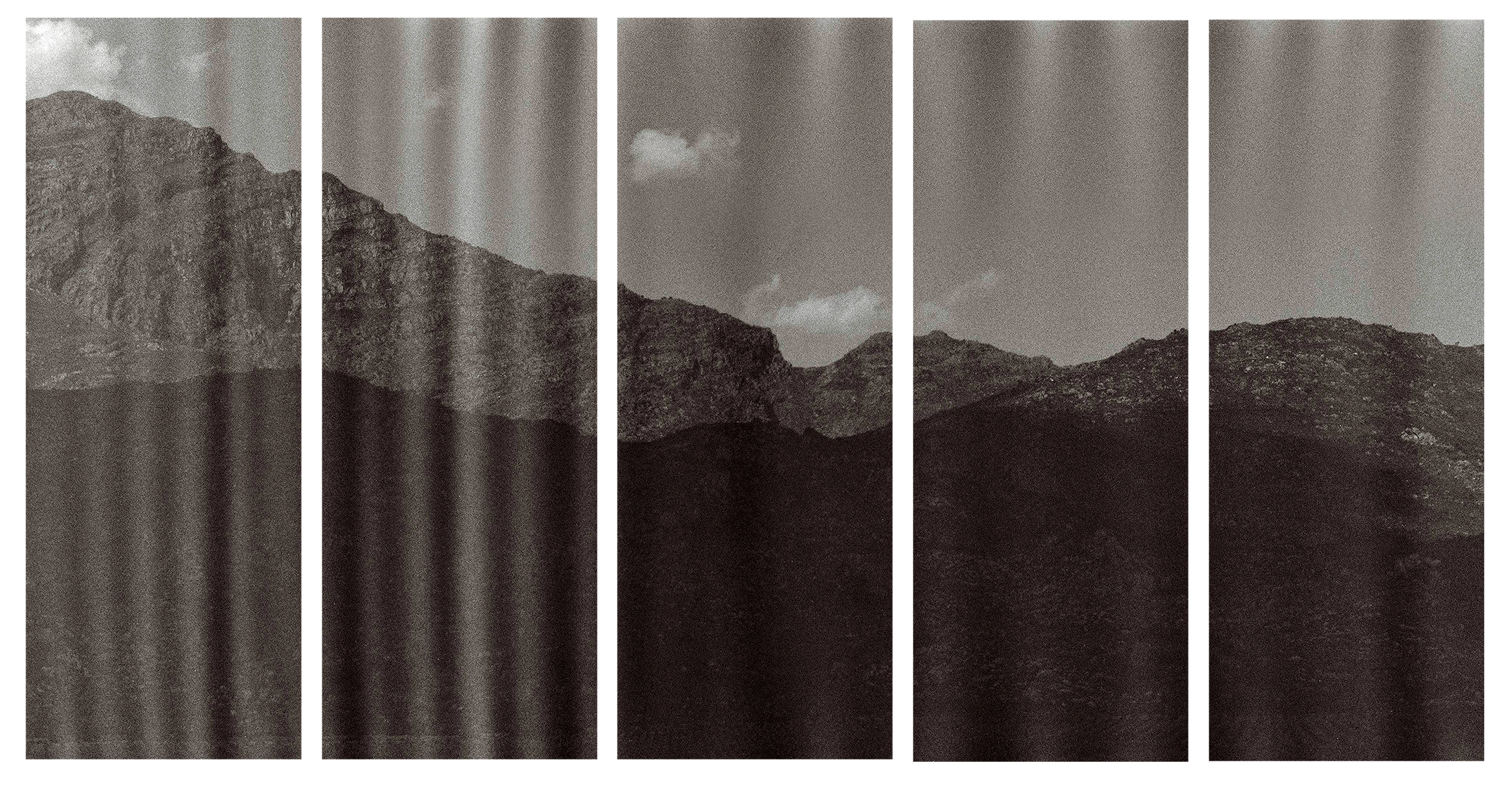

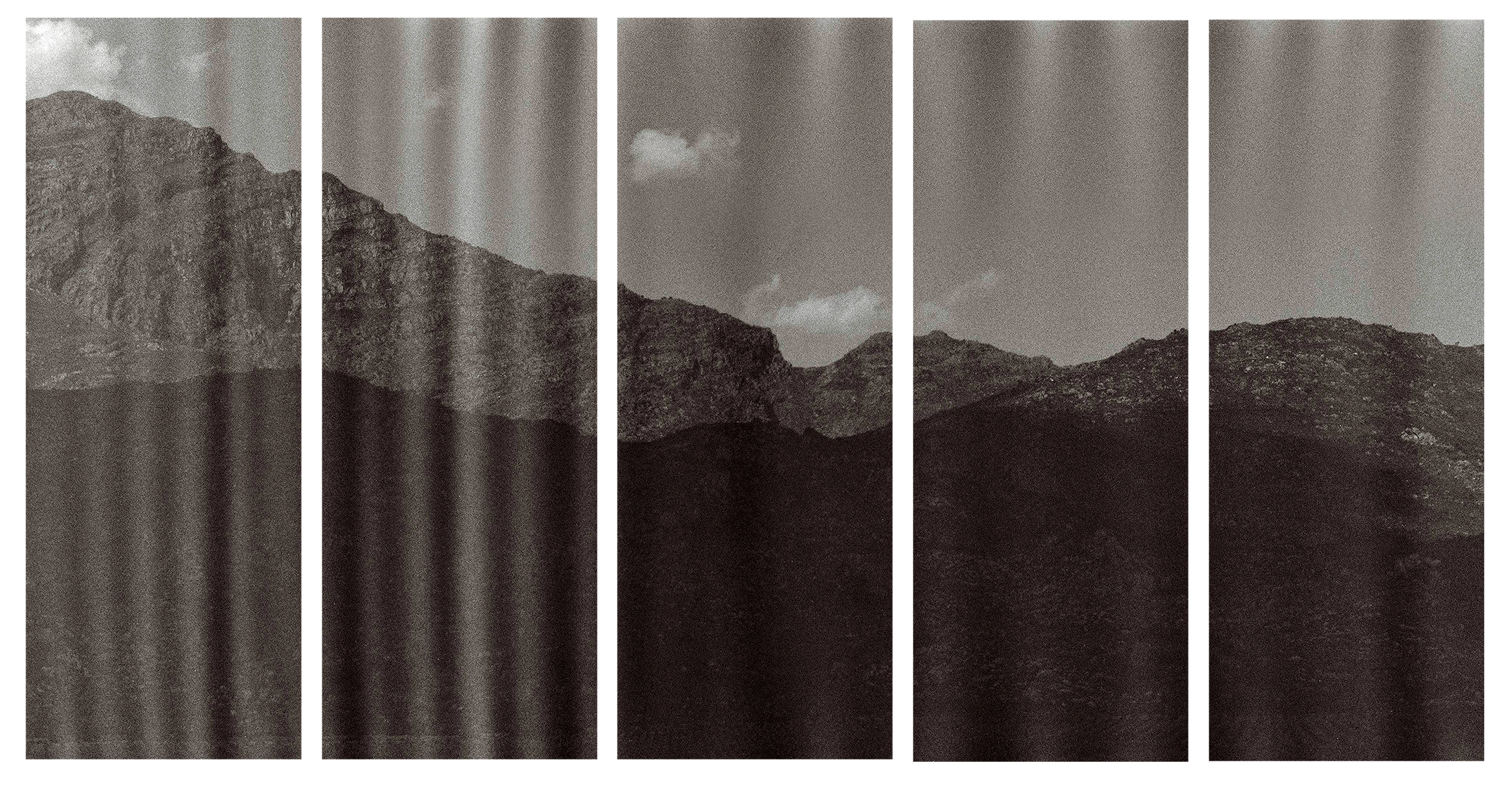

Alter Nature

2019 - ongoing

A change of habits will not alter nature — Aesop

A three-dimensional boxset gives the illusion of a real room.

The actors pretend to be unaware of the audience, separated by an invisible ‘fourth wall’ that is defined by the proscenium arch and the stage floor, which serves as a frame through which the audience observes theatrical events from a more or less unified angle.

Actors usually ignore the audience, focusing exclusively on the dramatic world. They remain absorbed in its fiction, in a state that Konstantin Stanislavski called ‘public solitude’ — the ability to behave as one would in private, despite being watched, or to be 'alone in public.’ The audience’s acceptance of this transparent fourth wall requires a suspension of disbelief in order to enjoy the fiction as though observing real events.

The history of photography has also assumed a subtle and implicit fourth wall, in particular the idea that the viewer is able to glimpse into a previously unknown ‘reality,’ be it of a place or person, which is packaged for immediate consumption.

Alter Nature takes its name from the cautionary fable by Aesop, titled The Raven and The Swan, in which a raven, through its overwhelming desire to look like the swan, gives up its way of life and attempts to mimic the swan, leading to its eventual demise. The story feels appropriate for our times, in which the unprecedented onset of AI-generated imagery and the echo chambers of social media and deep fakes have left many in a state of ‘public solitude,’ caught in the theatre of cyberspace.

These works deliberately break the fourth wall of the image-making process. Through the use of damaged monochrome celluloid film, fault lines and light seep into the images and create a meta-theatrical curtain within the landscape.

Through their analogue dissonance, these images question our relationship to the natural world, while subverting the illusionary nature of photography and its role in the manufacture of ‘truth.’

Enquire about editioned works here